Building for People, Not Prestige: The Humanist Vision of Jane Drew

In this new series, we focus on visionaries whose work was never just about aesthetics, but about shaping how we live. From architects to designers, their projects carried a quiet kind of utility, with structures and objects that not only looked beautiful but helped life unfold with more intention. By revisiting their stories, we look at how design can serve as both craft and compass, guiding us toward more conscious ways of living.

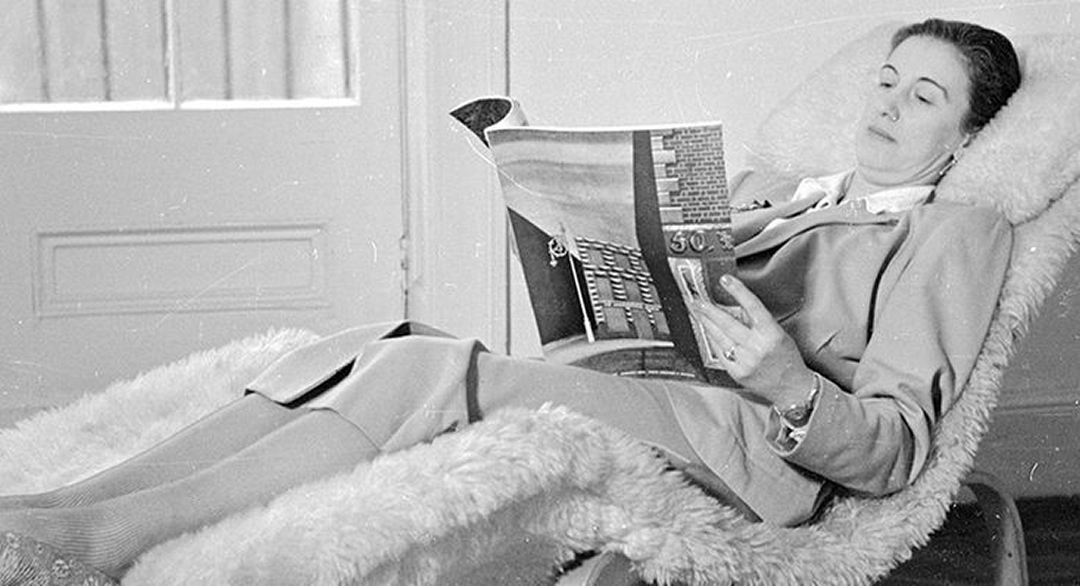

Jane Drew (1911–1996, UK)

In the same century that modernism sought purity of form, Jane Drew gave it a social conscience. To her, architecture was never about spectacle — it was about how people lived, and who got to live well. A pioneer of humanist design, she saw buildings as tools for equality, believing that thoughtful design could shape not just homes, but societies.

After the Second World War, Drew helped design some of Britain’s earliest social housing projects, bringing light, ventilation, and dignity to working-class neighborhoods recovering from devastation. She believed that architecture should serve the everyday — to make the act of living a little more graceful, a little more just. Later, her work extended far beyond the UK: in Ghana and India, she led projects that reimagined urban life for new nations finding their independence. Rather than exporting Western ideals, she absorbed the local climate, materials, and rhythms of life — designing buildings that belonged to their place and people.

Her philosophy was simple but profound: “Architecture must be useful before it is beautiful.” Yet in her hands, usefulness became its own quiet form of beauty — one that reflected empathy, balance, and respect. She understood that design’s moral power lay not in innovation alone, but in intention — in what it offered to those who would inhabit it.

As one of the first women to lead a major architectural practice, she challenged the profession’s hierarchies from within, mentoring younger designers and advocating for collaboration over ego. Her partnership on projects like Chandigarh with Le Corbusier exemplified her belief that architecture should be a collective language — one that serves humanity before aesthetics.

Why it inspires:

Jane Drew believed that progress should be built on inclusion. Her work endures not because it dazzled, but because it dignified — proving that architecture’s truest measure is not in the skyline, but in the lives it quietly improves. Through every school, home, and public space she helped create, Drew reminds us that to build well is to care deeply — and that beauty, at its most honest, begins with equality.